INDIGENOUS WOMEN PARTICULARLY AT RISK IN BRUTAL INTER-ETHNIC CONFLICT IN MANIPUR.

INDIAN GOVERNMENT MUST SPONSOR PEACE TALKS, PROSECUTE THOSE RESPONSIBLE FOR VIOLENCE, AND REHABILITATE AND RESETTLE THOSE AFFECTED BY THE VIOLENCE The violent conflict that broke out earlier this year between the Meitei and Kuki communities in Manipur, India, has resulted in the brutal deaths of at least 150 people (many believe the figure to be higher) and the displacement of tens of thousands. And despite the presence of the armed forces, who have also been accused of violence, inaction and partisan roles, the confrontations and violence continue. According to many observers, the lack of attention paid to the area, and the inaction on the part of the Central Government of Narendra Modi, is one of the root causes of the bloody clash between the armed groups belonging to the two peoples. Also critical is the lack of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of the Indigenous Peoples whose cultures and lands are being affected by forest conservation measures, energy and extractive projects, etc. The Center for Research and Advocacy, Manipur, CRA, is calling on the government to “institute [a]prompt and impartial investigation into all recorded cases of violence against women, farmers, youths, students, and media personnel, and to prosecute all those involved in perpetuating the violence against indigenous women in Manipur, including its security forces, who have a duty bearer role to protect women, youths and all Indigenous Peoples in Manipur”. The CRA also urges the Government of India and Government of Manipur to “take urgent steps to protect Indigenous Peoples, especially Indigenous women, from all forms of violence and discrimination in accordance with the UN Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination and Violence against Women, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples.” The Manipur based CRA, also calls attention to the increasing number of “cases of violence against women and youth perpetrated by the communities in conflict (and by the Indian security forces), despite the extensive militarisation of Manipur, and additional deployment of Indian security forces to Manipur in order to control the violence in the aftermath of the ethnic conflict that began on 3 May 2023.” The increase in violence against women is extremely serious, but is hardly new, as documented by this recent article in the Indian news portal Outlook: Manipur: How Violence Against Women Has Become A Weapon During Conflict. Land is Life is therefore calling for an end to violence in Manipur, and the resolution of the conflict through a negotiated settlement under the auspices of the Indian National Government. Land is LIfe echoes the call of the CRA for the investigation and prosecution of all those involved in crimes against Indigenous women, the excessive use of force on young people, and for the repeal of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, 1958. Land is Life also calls for the protection of Indigenous lands from damaging energy and extractive industries, and emphasizes the need for Free, Prior and Informed Consent of any Indigenous Peoples affected. MANIPUR Manipur is a State in the north east of India, with a long independent history dating back to AD 33. Except for the years of the British colonization from 1891 to 1947, the Kingdom of Manipur has generally been self-governed, and only became part of India as a consequence of the partition of the sub-continent when the British finally withdrew. More than 40 percent of Manipur’s people presently live below India’s poverty line. Violence broke out in May of this year between the State’s two major ethnic groups, the predominantly Hindu Meiteis, the traditional population of the area, who live in the valley (10% of the land area), and once formed over 50% of the population, but according to the 2011 Census of India, now only form 43% and the mainly Christian Kukis, brought in by the British to protect Manipur from the raids by the northern Naga tribes, who are still in active rebellion against India. Officially, the Kuki population, just 1% in 1891, had risen to 16% by 2011. Although the number is uncertain due to various factors including increased migration, there is little doubt that the Kukis, who together with Naga groups, live mainly in the hills that form the major part of the State’s land area, now form a considerable proportion of the population. The original dispute arose over a number of issues: the Meitie demand for restoration of Tribal Status and the violent response from opposing groups; the cross border impact of the ongoing conflict in Myanmar; and the Indian government’s pursuance of extractive industries and infrastructure projects, such as oil exploration, Kaladan Multimodal Transit Project, the trilateral highway project, etc. and the Sittwe to Gaya gas pipeline. Meitei people’s cultural concerns, and unchecked Kuki migration from Myanmar, where they are being persecuted by that country’s military rulers, are also factors. And besides the Kukis, the Meiteis are also concerned about the unabated migration of non Indigenous Peoples from other parts of India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. The Kuki have also revived the possibility of being granted a separate state administration and the unification of Kuki Zo territory, called the Zalengam, an idea that has been rejected by both the Meitei and Naga communities. Religion is also part of the mix, as between the 1961 and 2011 censuses of India, the share of Hindus in the State declined from 62% to 41%, while the share of Christians rose from 19% to 41%. The situation is extremely complex, with a risk the conflict could spread to Kuki and Meitei communities in neighboring Indian states, to Myanmar, and to Bangladesh. The violence, on the other hand, is quite clear. At the time of writing, it is estimated that some 70,000 people have been displaced, hundreds killed and injured on both sides, and entire villages burned to the ground. Both groups have also formed armed militias that are still not under control. And while the Indian central armed forces have been brought in, the state police activated, and

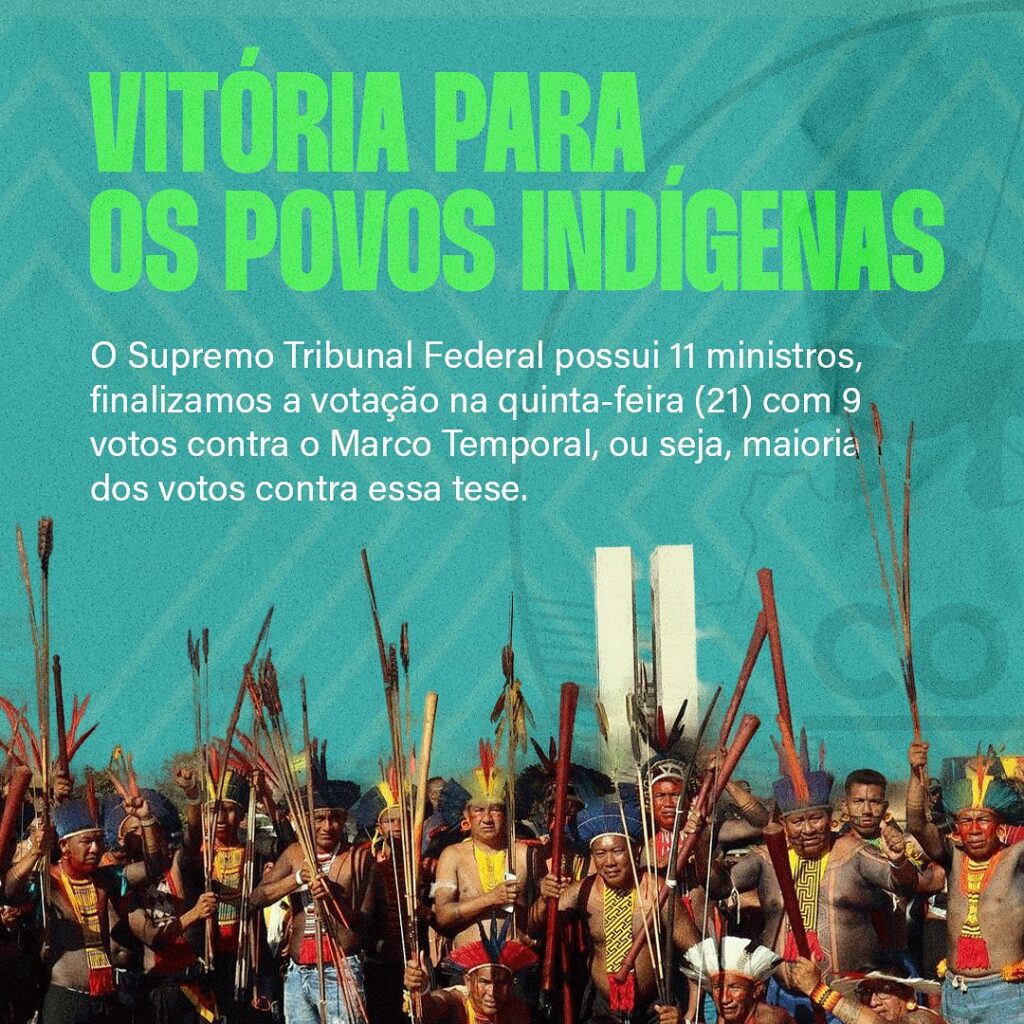

SENADO BRASILEIRO DESAFIA DECISÃO DO SUPREMO TRIBUNAL SOBRE MARCO TEMPORAL: COLOCA OS POVOS INDÍGENAS E A AMAZÔNIA EM GRAVE PERIGO.

A Constituição Brasileira de 1988, (Art. 231), concede aos Povos Indígenas o direito às terras que “tradicionalmente ocupam”, e desde essa data 761 tierras Indígenas foram reivindicados, embora apenas 475 tenham sido formalmente reconhecidas e regularizadas. O conceito de ‘Marco Temporal’ (promovido por legisladores ‘ruralistas’ que representam os interesses do agronegócio, dos mineiros e dos pecuaristas) procura limitar o direito aos povos que podem demonstrar que qualquer território reivindicado foi ocupado por eles antes da promulgação da Constituição . Portanto todas as reivindicações futuras, e mesmo algumas reivindicações passadas, estariam consequentemente sujeitas ao ônus da prova do “Marco Temporal”, representando um grave perigo para os Povos Indígenas do Brasil. No dia 21 de setembro deste ano, numa decisão amplamente celebrada pelos Povos Indígenas e seus aliados, o Supremo Tribunal Federal (STF) do país declarou inconstitucional tese de o “Marco Temporal”. Em resposta, a oposição dominada pelo Senado brasileiro aprovou recentemente o PL2903, em um claro desafio à decisão do STF e legitimidade deste. A lei não só ignora a decisão do Supremo Tribunal, como também viola os direitos dos Povos Indígenas consagrados na Declaração das Nações Unidas sobre os Direitos dos Povos Indígenas (UNDRIP), que afirma em seu art. 26, que: Os povos indígenas têm direito às terras, territórios e recursos que possuem e ocupam tradicionalmente ou que tenham de outra forma utilizado ou adquirido. Os povos indígenas têm o direito de possuir, utilizar, desenvolver e controlar as terras, territórios e recursos que possuem em razão da propriedade tradicional ou de outra forma tradicional de ocupação ou de utilização, assim como aqueles que de outra forma tenham adquirido. Os Estados assegurarão reconhecimento e proteção jurídicos a essas terras, territórios e recursos. Tal reconhecimento respeitará adequadamente os costumes, as tradições e os regimes de posse da terra dos povos indígenas a que se refiram Se o Senado dominado pela oposição tiver sucesso na sua tentativa de desafiar a decisão do “Marco Temporal” do STF, os danos resultantes para os Povos Indígenas, incluindo os 144 Povos Indígenas que vivem em Isolamento Voluntário, seriam graves. Os principais grupos indígenas e seus aliados da sociedade civil pedem, portanto, ao Presidente Lula da Silva que vete o Projeto de Lei 2.903/2023 em sua íntegra. Para LAND IS LIFE, a questão é clara: seja qual for a forma ou por qualquer mecanismo, o ‘Marco Temporal’ é uma grande ameaça não apenas para os Povos Indígenas e suas culturas, mas também para a floresta amazônica, pois abriria grandes extensões de terra a passíveis de desmatamento. Para LAND IS LIFE, os Povos Indígenas e as suas culturas têm o direito humano básico de existir e de florescer nos seus territórios. O Marco Temporal representa, portanto, uma terrível ameaça a esse direito e deve ser combatido. Os principais grupos indígenas e seus aliados da sociedade civil pedem, portanto, ao Presidente Lula da Silva que vete o Projeto de Lei 2.903/2023 na íntegra. Para LAND IS LIFE, a questão é clara. Seja qual for a forma, ou por qualquer mecanismo, o ‘Marco Temporal’ é uma grande ameaça, não apenas para os Povos Indígenas e suas culturas, mas também para a floresta amazônica, pois abriria grandes extensões de terra à possibilidade de desmatamento. Para LAND IS LIFE, os Povos Indígenas e as suas culturas têm o direito humano básico de existir e de florescer nos seus territórios. O Marco Temporal representa, portanto, uma terrível ameaça a esse direito e deve ser combatido.

BRAZILIAN SENATE DEFIES SUPREME COURT RULING ON MARCO TEMPORAL: PLACES INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND AMAZON IN GRAVE DANGER.

The Brazilian Constitution of 1988, (Art. 231), grants Indigenous Peoples the right to land they have “traditionally occupied”, and since that date 761 territories have been claimed, although only 475 have been formally recognized and adjudicated. The ‘Marco Temporal’ concept (promoted by ‘Ruralist’ legislators who represent the interests of agribusiness, miners and cattle ranchers) seeks to limit the right to those Peoples who can demonstrate that any territory claimed was occupied by them before the enactment of the Constitution. All future, and even some past claims, would consequently be subjected to the ‘Marco Temporal’ burden of proof, representing a clear and present danger to Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples. On September 21st of this year, in a ruling widely celebrated by Indigneous Peoples and their allies, the country’s Supreme Court declared the ‘Marco Temporal’ concept to be unconstitutional. In response, the opposition dominated Brazilian Senate recently passed PL2903, or the ‘Marco Temporal’ legislation, in both clear defiance of the Supreme Court’s decision, and as a challenge to the legitimacy of the Court itself. The law not only ignores the Supreme Court’s ruling, it also contravenes the rights of Indigenous Peoples enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which states in Art. 26, that: Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired. 2. Indigenous peoples have the right to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership or other traditional occupation or use, as well as those which they have otherwise acquired. 3. States shall give legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories and resources. Such recognition shall be conducted with due respect to the customs, traditions and land tenure systems of the indigenous peoples concerned There is no doubt that if the opposition dominated Senate succeeds in its attempt to defy the Supreme Court’s ‘Marco Temporal’ ruling, the resulting damage to Indigenous Peoples, including 144 Peoples living in Voluntary Isolation, would be grave. The major Indigenous groups and their civil society allies are therefore calling on President Lula da Silva to veto Bill 2903/2023 in its entirety. For LAND IS LIFE, the issue is clear. In whatever form, or by whatever mechanism, the ‘Marco Temporal’ is a major threat, not only to Indigenous Peoples and their cultures, but also to the Amazon rainforest, as it would open up major tracts of land to the possibility of deforestation. For LAND IS LIFE, Indigenous Peoples and their cultures have a basic human right to exist, and to flourish within their territories. The Marco Temporal therefore represents a dire threat to that right, and must be resisted.

LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS, AGENTES EN LA LUCHA CONTRA LA CRISIS CLIMÁTICA

Jorge Basilago 26 septiembre 2023 https://www.opendemocracy.net/es/pueblos-indigenas-agentes-lucha-crisis-climatica/ La crisis climática es una realidad que ya nadie puede desconocer. Tampoco existe duda alguna acerca de la seriedad del fenómeno para la vida de los Pueblos Indígenas, explica José Proaño, Director de Programas de Land is Life para América Latina. “Todos seremos afectados de manera dramática y aquí, en América Latina, encontrarnos en la región del planeta que genera menos emisiones de CO2, tampoco impide que las consecuencias del cambio climático sean cada vez más visibles y dramáticas. Más grave aún, es que la crisis impactará con mayor severidad a los pueblos indígenas, con especial énfasis en las mujeres de esas comunidades.” La respuesta, según Proaño, radica en tomar decisiones difíciles, como cuando la población ecuatoriana optó por dejar el petróleo bajo tierra, en la Consulta Popular sobre la explotación hidrocarburífera en el Parque Nacional Yasuní. Es indudable que el mundo tiene que superar la era de los combustibles fósiles, y para los Pueblos Indígenas de todo el mundo, incluyendo los Pueblos en Aislamiento Voluntario, mientras más rápido suceda eso, será mejor. Su supervivencia puede depender de ello. La crisis climática: impacto global, daños particulares A comienzos de septiembre de 2023, la Organización Meteorológica Mundial (OMM) presentó un informe sobre las temperaturas récord del verano boreal precedente. Según este organismo, el trimestre junio-julio-agosto fue el más caluroso en la historia del planeta tierra: en conjunto, este período resultó 1.5°C más cálido que el promedio preindustrial de 1850-1900. Este dato llevó al Secretario General de la ONU, António Guterres, a concluir que “el colapso climático” mundial ha comenzado. “Los científicos han advertido hace mucho tiempo sobre lo que desencadenará nuestra adicción a los combustibles fósiles.” Al ritmo en que aumentan los desastres de origen meteorológico – las inundaciones por esta causa se incrementaron un 134% entre 2000 y 2023 –, también se hacen más evidentes sus consecuencias negativas para poblaciones rurales e indígenas en regiones como el continente asiático, los pequeños estados insulares y el África subsahariana. Los países con menor responsabilidad en la aceleración del cambio climático padecen sus consecuencias con mayor crudeza De hecho, la Cumbre Climática de África, reunida en Kenia en septiembre de 2023, determinó en su Declaración Final que ese continente “se está calentando más rápido que el resto del mundo”. Las autoridades gubernamentales participantes del encuentro, manifestaron asimismo su preocupación porque “muchos países africanos enfrentan cargas desproporcionadas y riesgos crecientes relacionados con el cambio climático”. Por lo general, los países con menor responsabilidad en la aceleración de este proceso padecen sus consecuencias con mayor crudeza, pero a la vez albergan gran parte de los activos naturales y culturales que podrían contribuir a atenuarlas. Características que desvelan, simultáneamente, otras inequidades históricas: las naciones africanas, por ejemplo, concentran en conjunto cerca del 40% de los recursos de energías renovables del mundo, pero solo recibieron el 2% de la inversión total en ese ámbito, durante la última década. Algo similar sucede con los pueblos indígenas, a los que un estudio de la Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT) consideró “fundamentales para el éxito de las medidas y las políticas dirigidas a mitigar el cambio climático”. En principio, porque son alrededor de 370 millones de personas en todo el planeta, situadas “a la vanguardia de un modelo económico moderno basado en los principios de una economía verde sostenible”, las que pueden impulsar un cambio de matriz productiva a partir de sus conocimientos tradicionales. Sin embargo, la OIT indicó también que estas poblaciones concentran otras seis características que las vuelven especialmente frágiles ante un eventual colapso del clima. La primera y más dañina de ellas es la pobreza, que acosa a un 15% de sus integrantes; al igual que la dependencia de los recursos naturales; la vulnerabilidad de las regiones geográficas y ecosistemas en que viven; la potencial obligación de migrar por la destrucción de esos hábitats; las desigualdades de género y la falta de reconocimiento como personas indígenas, de sus derechos e instituciones. Pueblos Indígenas africanos como los Maasai de Tanzania, por ejemplo, ya han sido desplazados de sus territorios y confinados al borde del hambre a partir de políticas que restringen sus actividades de pastoreo en “áreas de conservación”. Advertidos de esta circunstancia, los gobernantes reunidos en la cumbre africana instaron a “apoyar a los pequeños agricultores, Pueblos Indígenas y comunidades locales en la transición a economías sustentables dado su papel clave en la gestión de los ecosistemas”. Pero aun así, múltiples culturas ancestrales, en todo el mundo, pueden afrontar idéntico destino a corto o mediano plazo. Los Maasai de Tanzania han sido desplazados de sus territorios y confinados al borde del hambre. Foto: Land is Life América Latina Los Pueblos Indígenas de América Latina tampoco escapan de los impactos de la marginación y el cambio climático. “Mientras en el mundo se discuten las formas de parar el cambio climático, las empresas transnacionales no han hecho ningún esfuerzo por bajar las presiones sobre nuestros territorios”, sostuvo Leonidas Iza, presidente de la Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (Conaie) en la Cumbre Climática COP27 de Egipto, a fines de 2022. Por su parte, para Germán Freire, autor de la investigación “Latinoamérica Indígena en el Siglo XXI”, publicada por el Banco Mundial (BM), no siempre el porvenir es sinónimo de aprendizaje: “Cuando escribimos el informe en 2015, nos impactó que, a pesar de los avances de las décadas pasadas en términos de marcos legales y representación, los pueblos indígenas seguían rezagados detrás de todos los demás en casi todos los aspectos. Desde entonces, las cosas han empeorado aún más, debido a los efectos acumulativos de la pandemia, el cambio climático y el crecimiento de la desigualdad. Los pueblos indígenas necesitan estar al volante de su propio desarrollo para que este sea sostenible y resiliente”. Sobre un estimado de 42 millones de personas indígenas en América Latina, un 43% es pobre, mientras que el 24% sufre pobreza extrema En sintonía con otros análisis globales, el documento del BM puso el foco en la notoria

THE MARCO TEMPORAL IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL: LAND IS LIFE CONGRATULATES BRAZIL’S INDIGENOUS PEOPLES ON A CRUCIAL VICTORY

On Thursday September 21st, the Brazilian Supreme Court voted against the so called ‘Marco Temporal’, which would have forced the country’s Indigenous Peoples to demonstrate that any territories claimed as traditional, had been occupied by them prior to the Brazilian Constitution of 1988. Court magistrate Carmen Lucia stated that Brazilian Society had an unpayable debt to Indigenous Peoples. Article 231 of the Constitution grants Indigenous Peoples the right to land they have “traditionally occupied”, and according to the National Indigenous Peoples Foundation (FUNAI), 761 territories covering about 1.2 million square kilometers (almost 14% of Brazil’s territory) have in fact been claimed. But of these the government has recognized only 475, despite the fact that the 1988 Constitution also guaranteed that all claims be resolved within five years. The legal argument, promoted by the ‘Ruralist’ block of legislators representing the interests of agribusiness, miners and cattle ranchers, would have made that constitutional right time dependent, and placed the burden of proof on the Indigenous Peoples themselves. Such proof may have been difficult to produce: one of the principal reasons being that many Indigenous Peoples were forced to keep moving in order to avoid conflict with agribusiness, and illegal loggers and miners, the very people that today want to limit their rights There is little doubt that a vote in favor of the ‘Marco Temporal’ would have been disastrous for the country’s Indigenous Peoples, including the Amazon’s 144 Peoples in Voluntary Isolation, who live mainly in territories created to protect them. But the fate of Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples was not the only thing in play, the entire Amazon forest would also have been dramatically affected. Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon is a global concern, and after the devastating effects of the Bolsonaro government’s policies, in the first year of President Lula da Silva’s third term in office, the world has seen some long desired success in reducing deforestation rates. But under the ‘Marco Temporal’ this would have represented an extremely short term victory in a much longer term war. For example, it has been estimated that up to 95% of Indigenous territories could have been affected, contributing massively to the climate crisis. According to environmental scientist Ana Claudia Rorato of Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research, and conservation biologist Celso Silva-Junior of the Federal University of Maranhão, some 87,000 to 1 million square kilometers of forest could be left unprotected. In other words, left at the mercy of the farmers, loggers, miners, cattle ranchers and others that have fought against recognizing Indigenous territories. Clearing these forests would have caused a massive increase in carbon emissions, and have moved the Amazon closer to a tipping point: a condition which would change the hydrologic cycle and begin a process in which rainforests would be turned into much dryer savanna. In sum, the ‘Marco Temporal’ would have had devastating consequences for both Brazilian Indigenous Peoples, and the Amazon rainforest and its priceless biodiversity. Land is Life applauds the combined efforts of Brazilian Indigenous Peoples and civil society organizations in the fight to avoid an extremely dangerous and short-sighted policy. However, we must continue to be vigilant, as despite this crucial victory the Ruralist legislative block will not disappear, and will surely be working hard to find other ways to achieve its objectives. Fotos @Coiabamazonia

LAND IS LIFE CONDAMNE LE MASSACRE DES AGRICULTEURS DANS LA PROVINCE DE L’ITURI DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE DÉMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO (RDC)

Land is Life exhorte le gouvernement de la République Démocratique du Congo, en particulier le gouvernement militaire provincial de l’Ituri et l’administration militaire territoriale de Mahagi, à assurer la sécurité et la protection de la population résidant dans la chefferie de Mokambu. Ces individus font face à des menaces de mort importantes du fait des actions militaires du groupe CODECO dans le territoire de Mahagi. Dans la soirée du jeudi 1er septembre 2023, cinq ouvriers agricoles, membres des ménages du Groupement de Ruvinga en Province de l’Ituri, ont été massacrés par les milices armées de la CODECO (Coopérative pour le développement du Congo). Vingt-cinq personnes ont été blessées, sept ont été prises en otage lors du pillage de leurs propriétés, et plus de 200 agriculteurs du groupement de Ruvinga ont été contraints de fuir leurs terres agricoles. CODECO avait déjà commis un autre massacre dans le village de pêcheurs de Musekere, qui fait partie du Groupement Sumbuso, situé dans la chefferie de Bahema Nord, dans la région de Djugu de la même province. Selon des sources locales, le 21 août, six personnes, qui incluent un enfant et trois femmes ainsi que deux hommes, auraient été tuées. Selon des données vérifiables provenant d’organisations locales de la société civile de la région, la milice CODECO a également grièvement blessé au moins six autres personnes, dont des agriculteurs, des pêcheurs et des femmes. En juillet 2023, la CODECO a aussi tué au moins 46 civils, dont la moitié était des enfants, lors d’un raid contre le camp de Lala pour personnes Hema déplacées. Des soldats congolais et des soldats de maintien de la paix des Nations Unies étaient apparemment présents dans la ville voisine de Bule, mais ne sont pas intervenus. CODECO fait partie d’un groupe de milices armées opérant en RDC, un pays impliqué dans un conflit armé extrêmement sanglant et de longue durée, connu sous le nom de première et deuxième guerres du Congo, qui a coûté la vie à six millions de personnes depuis 1996. Le groupe CODECO, initialement fondé comme coopérative agricole, est devenu une milice active dans le conflit de l’Ituri – une période de violence intense qui a duré de 1999 à 2003. Le groupe a depuis subi un nombre de transformations et est toujours actif malgré son implication dans divers processus de paix.

LAND IS LIFE CONDEMNS MASSACRE OF FARMERS IN ITURI PROVINCE OF DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO (DRC)

On the evening of Thursday, September 1st, 2023, five agricultural workers who were members of the households in Ruvinga Groupment in Ituri Province were massacred by CODECO armed militias. Twenty-five people were also injured, seven were held hostage during the looting of their properties, and over 200 farmers from the Ruvinga Groupment were forced to flee their agricultural lands. CODECO had previously committed another massacre in the fishing village of Musekere, which is part of the Sumbuso Groupement located in the chiefdom of Bahema Nord in the region of Djugu in the same Province. According to local sources, on August 21st six people, including a child and three women as well as two men in uniform, were reported killed. According to verifiable data from local civil society organizations in the region, the CODECO militia also seriously injured at least six more people, including farmers and fishermen and women. In July of 2023 CODECO also killed at least 46 civilians, half of them children, in a raid on the Lala camp for displaced Hema people. Congolese soldiers and United Nations peacekeepers were apparently present in the nearby town of Bule, but did not intervene. CODECO is part of a group of armed militias operating in the DRC, a country that has been involved in a long drawn out and extremely bloody armed conflict, known as the first and second Congo Wars, that has claimed the lives of six million people since the 1996. The CODECO group, initially founded as an agricultural cooperative, became an active militia in the Ituri Conflict – a period of intense violence that lasted from 1999 to 2003. The group has since undergone a number of transformations and despite involvement in various peace processes is still active. Land is Life urges the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo, specifically the Ituri provincial Military government and the Mahagi territorial military administration, to take immediate action to ensure the safety and protection of the population residing in Mokambu Chiefdom. These individuals face significant threats to their lives as a result of the military actions of the CODECO group within the Mahagi territory. Foto: CODECO fighters in Eastern DRC. humanglemedia.com

AFRICA CLIMATE WEEK AND SUMMIT ARE OPPORTUNITIES FOR PROGRESS: BUT WHO WILL BENEFIT?

African Indigenous Peoples are being seriously affected by the climate crisis. Africa Climate Week (4th– 8th September) and the continent’s first Climate Summit (4th – 6th) offer a chance for action, but serious doubts have emerged about exactly who is controlling the agenda, and whether the decisions taken will favor Africa’s Indigenous Peoples, who are the most impacted and most in need of support. Climate change is a major issue everywhere, but for Indigenous Peoples, many of whom depend on the local environments for their livelihood, the stakes are even higher. In many African countries the issue is critical. In Burkina Faso, for example, where approximately 90% of the population makes its living through subsistence agriculture and livestock, rising temperatures will place a huge burden on those already on the margins of sustainability. Indigenous Peoples and women are particularly at risk. In the more arid northern regions of this land-locked country, where the Peul and Tuareg peoples live, water scarcity has been magnified by the severe drought of 2022, and even a slight rise in temperature could be mortal; while in the south, flooding has wreaked havoc with crops and drinking water supply, even in the capital, Ouagadougou. Subsistence agriculture and livestock are crucial for the country’s Indigenous Peoples, and rising temperatures will no doubt lead to more displacement, poverty, and migration to already overburdened cities. The major question is how to tackle the problem at a national and regional level. Given the context of violence, the recent military Coups D’état of 2022, and other in the region (Mali, Niger and now Gabón), in Burkina Faso it’s not really feasible to expect the national government to take the lead, says Saoudata Wallet, an indigenous Tuareg woman and Secretary General of the Burkina Faso and Mali Tin Hinane Association. In her country, she adds, it is really up to the people, particularly women’s organizations, to keep up the pressure, but even here, the regional violence, which also includes attacks by Islamic extremists, has affected people’s ability to mobilize. One opportunity to make the concerns of indigenous peoples heard, is Africa Climate Week (ACW), which will take place from the 4th to the 8th of September in Nairobi, Kenya, in parallel with the first Africa Climate Summit (ACS) which will also take place in that city between September 4th and 6th. The Summit is co-hosted by The Kenyan government and the African Union, and as of mid-August, 15 African Heads of State and government had confirmed their participation. The events are part of the run up to the 28th UN Climate Change Conference (COP 28), to be held between the 30th of November and the 12th of December in Dubai, capital of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and will provide regional contributions to the first Global Stocktake, seen as fundamental in fulfilling the Paris Agreement goals. Although Wallet agrees most international conferences are forums for declarations rather than actions, she is convinced the presence of women and Indigenous Peoples is crucial for both the Africa Climate Summit and the parallel climate week events. “We have to be there to demand that our voices be heard”, she says, while recognizing that actually getting to the conferences can be a problem given the difficulties some experience in obtaining visas and financing in order to travel. And as she points out, it’s a long way from Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, to Nairobi. So walking is evidently not an option. As with other international proceedings, the presence and, most importantly the input, of Indigenous Peoples will be crucial to both the success of these events and to that of the COP 28 itself. For Indigenous Peoples, says Wallet, resilience to climate change is rooted in their traditional knowledge and ability to adapt to environmental change based on their in-depth knowledge of the land. However, she adds, a serious obstacle is that Indigenous and women’s voices are generally downplayed, if not ignored entirely. Many Indigenous Peoples in Africa are not even recognized as such by the countries in which they live, in many cases being seen as dividing rather than unifying recently formed States, some even being classified as ‘foreigners’ in their own lands. Women also face major difficulties in the region, says Wallet, due to the violence that has been plaguing the Sahel region, and for anyone with an independent voice, the possibility of a backlash is very difficult to face. Another major fear is that rather than being simply a space for posturing, or in the best of cases actually helping African countries’ vulnerable populations to adapt and survive, the host Kenyan government is looking at the upcoming events as a possibility for investments and boosting the continent’s ‘green economy’. According to Kenya’s environment and climate change cabinet secretary Soipan Tuya, the plan is to “end the ‘blame game’ between developed and developing countries, and to unlock the investments Africa needs to tap into its potential and resources to support global decarbonisation efforts.” All of which raises doubts about who is really going to control the discussions and recommendations. A particular concern is the involvement of U.S. consulting giant McKinsey. An open letter signed by more than 400 African civil society groups has accused the firm of having unduly influenced the summit by “pushing a pro-West agenda and interests at the expense of Africa”, claiming that the summit’s agenda promotes “concepts and false solutions [that] are led by Western interests while being marketed as African priorities”. This, rather than prioritizing the needs of African populations, such as strengthening resilience in the face of rising temperatures, and find finding ways to help poorer countries deal with financial losses and damages due to the climate crisis or even dealing with the issue of fossil fuel phase out. According to Augustine Bantar Njamnshi, of the Pan African Climate Justice Alliance “We had a lot of hope this summit would put African priorities at the heart of climate negotiations, notably adaptation finance. It should have been

ECUADOR’S YASUNÍ REFERENDUM: between business as usual and the urgent need for a post oil strategy

Fifty one years have now transpired since the day, June 26, 1972, that Ecuadorian television viewers saw “the first oil barrel being filled with the country’s recently discovered ‘black gold’. It was the beginning of a so-called oil ‘boom’, which in 2023, now appears to be coming to an end. The old wells are no longer as productive as they were; and new reserves are not only increasingly difficult to find, they will almost certainly be located in areas close to Amazon protected areas, where the social and environmental costs of exploiting them will be so much greater. Surprisingly perhaps, the problem is not simply one of supply. According to the forecasts of the International Energy Agency (IEA), in a few years we will reach the global demand high point, or so-called ‘Peak Oil‘, undoubtedly due to the changes brought about in Europe due to the war in Ukraine. From there demand is expected to keep falling. It now appears that for Ecuador the eagerly awaited energy transition, necessary due to the pressing need to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, and avoid an increase in the planet’s temperature, is now knocking on the door. A climate change that, it is worth mentioning, would put many people at risk, principally the most impoverished and marginalized sectors. The dilemma for the country is how to manage this energy and economic transition internally, and with no contingency plan in sight. The situation is delicate, however, because the other side of the coin is a country where the formal employment rate barely reaches 3 out of 10 people of working age; and where, according to the World Bank, in 2022 GDP per capita reached only US$5,590, and where oil revenues form a substantial percentage of the national income. It is obvious, therefore, that stopping all oil production is not an immediate option, while at the same time it is essential to design and implement a post-oil policy in the medium term. The million dollar question, is whether political will to do so exists. The Consultation on the Yasuní Park and oil. The answer to the question is, no, at least for now. But with a popular consultation called for August 20th, 2023, the country is now facing the possibility of a turning point in its history of oil dependence. The current question posed is the same as the one raised in a frustrated 2013 plebiscite: whether the oil from oil Block 43, located to the northeast of the Yasuní National Park, one of the areas of greatest biodiversity on the planet, should be kept in the ground. A Yasuní, it is worth mentioning, that has been classified as a “Pleistocene refuge”, declared by Unesco as a World Biosphere Reserve, and is also home to peoples in voluntary isolation: the Tagaere, Taromenane and Dugakaere. The consultation is – and always was – conceived as a turning point in the search for a post-oil future for Ecuador. It will also take place almost 10 years after the previous attempt to prevent exploitation of the same Block 43, an initiative that was clearly, and illegitimately undercut by the Constitutional Court of the time. Only a sustained campaign in the face of a highly politicized national institutional structure, and confrontations with a succession of governments, was able to persuade the current Constitutional Court to issue a favorable opinion for the second version of the referendum on May 9th of this year. But while the question is identical, the political and economic conditions in which the consultation will take place are very different from those in play 10 years ago. The Block’s oil wells have been in operation since 2016, coming within meters of the buffer area of the Park’s Intangible Zone, where the previously mentioned isolated peoples live. Putting an end to oil extraction in Block 43 will consequently not only costs in terms of lost income, but also in terms of the removal of the infrastructure; which is one of the hottest points of the debate. But these costs are fixed, and no matter who wins the vote, will have to be paid, now or whenever the oil wells run dry. In Yasuní National Park, the options that the country has are seen more clearly. On the one hand, is the already traditional policy of living off oil, which does offer the possibility of sustaining social security programs for the bulk of the population, which as the poverty rate testifies has not guaranteed them, and implies an active participation in the global climate crisis. On the other hand, there is the need for a post-oil policy focused on healthier ways of living, on the need to preserve biodiversity, to reduce the impacts of climate change – which, it should be noted, will affect the most unprotected segments of the population – and protect nomadic Indigenous Peoples who live in voluntary isolation. Can the extermination of ‘peoples in isolation’ be avoided? The aforementioned Intangible Zone, located meters from block 43, is an area of Yasuní National Park reserved for protecting and guaranteeing the conditions vital for the survival of Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact (PIACI). A development model based on the extraction of natural resources, which includes the infrastructure required to obtain the county’s ‘black gold’, clearly endangers Indigenous Peoples and those in voluntary isolation. The forest was their home long before the arrival of the colonizers and their extractive projects. With more ecological awareness than in current times, on July 26, 1979 – and that with a military triumvirate in power –, the Yasuní National Park territory was established, which according to the Ministry of the Environment’s website implies “protecting this ecological zone of one or more ecosystems for present and future generations; excluding exploitation or occupation not linked to the protection of the area; and providing the basis for visitors to make spiritual, scientific use (of the area)”. However, and always with the unfulfilled justification that “the area’s oil reserves will help us

CONSULTA PARQUE NACIONAL YASUNÍ: Entre el camino de siempre y la necesidad urgente de una política pospetrolera

Han pasado 51 años desde que, el 26 de junio de 1972, se documentó para la televisión nacional la forma en que “el oro negro llenaba el primer barril de petróleo”. “el oro negro llenaba el primer barril de petróleo”. Ese fue el inicio del denominado ‘boom’ petrolero en el Ecuador, que ahora, en 2023, parece estar llegando a su fin: los pozos antiguos ya no rinden como antaño; y las nuevas reservas no sólo son cada vez más difíciles de encontrar, sino que, si existen, se hallarán en zonas cercanas a las áreas amazónicas protegidas, donde los costos sociales y ambientales de explotarlas serán mayores. Claro que, quizás de manera sorpresiva, el problema no es solamente de oferta. Según los pronósticos de la Agencia Internacional de la Energía (AIE), a nivel global llegaremos muy pronto al punto más alto de la demanda, el llamado ‘Peak Oil’, sin duda debido a los cambios forzosos en Europa por la guerra en Ucrania. Por fin, la largamente anhelada transición energética, necesaria debido a la apremiante necesidad de reducir la emisión de dióxido de carbono (CO2) y evitar un incremento en la temperatura del planeta, ahora está tocando a nuestra puerta. Un cambio climático que, vale mencionar, pondría en riesgo a mucha gente, principalmente a los sectores más empobrecidos y marginados. El dilema para el Ecuador es cómo manejar esa transición energética dentro del territorio nacional, en el contexto mencionado, sin plan de contingencia a la vista. La situación es delicada, porque al otro lado de la moneda está un país donde la tasa de empleo formal apenas llega a 3 de cada 10 personas en edad laboral; y donde, según el Banco Mundial, el PIB per cápita alcanzó sólo a US$5,590 en 2022. Es decir: los ingresos petroleros forman un porcentaje sustancial del presupuesto. Es obvio, por tanto, que dejar de producir petróleo no es una opción en lo inmediato, pero al mismo tiempo resulta imprescindible diseñar e implementar una política pospetrolera a mediano plazo. La pregunta del millón es si existe la voluntad política para hacerlo. La Consulta sobre el Parque Yasuní y el petróleo. La respuesta a la pregunta es no, al menos por ahora. Pero el país hoy se encuentra ante un posible punto de inflexión en su historia de dependencia petrolera, con la consulta popular convocada para el 20 de agosto de 2023. La interrogante actual es la misma que la planteada en el frustrado plebiscito de 2013: si se debe mantener bajo tierra, o no, el crudo del Bloque 43, situado al noreste del Parque Nacional Yasuní, una de las áreas con mayor biodiversidad del planeta. Un Yasuní, clasificado como “refugio del pleistoceno” y declarado por la Unesco como Reserva Mundial de la Biósfera, que es también hogar de Pueblos Indígenas en aislamiento voluntario: los Tagaere, Taromenane y Dugakaere. La consulta es –y siempre fue- concebida como un punto de giro para el futuro pospetrolero del Ecuador. Y se realizará casi 10 años después del primer intento de evitar la explotación de petróleo en el sitio mencionado, que fue desviado de manera claramente ilegítima por la Corte Constitucional de ese entonces. Sólo una campaña sostenida, ante la politizada institucionalidad nacional y en medio de enfrentamientos con varios gobiernos de turno, pudo lograr que la Corte Constitucional actual emitiera, el pasado 9 de mayo, un dictamen favorable para la segunda versión de la consulta. Pero más allá de que la pregunta sea idéntica, las condiciones políticas y económicas en que se realizará esta vez la consulta son muy distintas de las originales. Los pozos petroleros del bloque están en operación desde el 2016, incluso llegando a metros del área de amortiguamiento de la llamada Zona Intangible del Parque, donde viven los pueblos aislados. Por ende, dejar de extraer el petróleo del Bloque 43 no sólo tendrá sus costos en términos de ingresos perdidos, sino también en lo relacionado con el retiro de la infraestructura; uno de los puntos más álgidos del debate. Pero estos costos son fijos, y tendrán que pagarse ahora o más tarde. En el Parque Nacional Yasuní, por tanto, hoy se ven con mayor claridad las opciones que tiene el país. Por un lado, la ya tradicional política de vivir del petróleo, que implica participar activamente en la crisis climática global y que, si bien ofrecería la posibilidad de sostener programas de seguridad social para el grueso de la población, no los ha garantizado más que esporádica y coyunturalmente. Por otro lado, tenemos la necesidad de diseñar una política pospetrolera enfocada en buscar formas más sanas de vivir sin el crudo, en la necesidad de preservar la biodiversidad, reducir los impactos del cambio climático – que, cabe destacar, afectarán con mayor fuerza a las franjas más desprotegidas de la población – y en proteger a los Pueblos Indígenas nómadas que viven en aislamiento voluntario. ¿Se puede evitar el exterminio de los ‘pueblos libres’? La ya mencionada Zona Intangible, ubicada a metros del bloque 43, es un espacio reservado, destinado a la protección y a garantizar las condiciones naturales para la sobrevivencia de los Pueblos Indígenas en Aislamiento y Contacto Inicial (PIACI). El modelo de desarrollo extractivo y toda la infraestructura que demanda la obtención del ‘oro negro’, pone en peligro a los pueblos originarios y en aislamiento voluntario. La selva es su casa, desde mucho antes de que llegaran los colonos y sus proyectos extractivos. Con más consciencia ecológica que en los tiempos actuales, el 26 de julio de 1979 ¬––con un triunvirato militar en el ejercicio del poder del Estado–, se declaró y se delimitaron los territorios del Parque Nacional Yasuní, lo que implica“proteger esta zona ecológica de uno o mas ecosistemas para las generaciones presentes y futuras; excluir la explotación u ocupación no ligadas a la protección del área; y proveer las bases para que los visitantes puedan hacer uso espiritual, científico (del espacio)”, , según señala el Ministerio de Ambiente en su página web. No obstante, y siempre bajo la